There’s one room at Shades Cahaba Elementary that students beg to go in. And when they walk past it, they peek in, always wanting to know what is going on.

Inside, a Lego wall allows kids to build out structures vertically, often famous buildings they replicate from idea cards. On a peg board in the back, screwdrivers and hammers hang ready for projects. Green screens come down to film the school’s weekly news broadcast. Brainstorming happens on tables, cabinets and boards with dry erase markers. Stackable stools are moved out of the way for group work on floors. Even benches for seating look like a keyboard “delete” button. Everything about the makerspace and its contents is designed for learning, for releasing ideas, for play, for experimentation—especially for technology, science, mathematics and art.

“The makerspace movement came from getting back to the tinkering and playful mind-set of learning by discovery,” assistant principal Wendy Story says. “It exposes them to more future technologies to prepare them for the world they will enter into because it’s not a world we have ever prepared for.”

But what the kids remember most is that it’s fun. “There’s a buzz in this room,” Wendy says. “Kids are enthralled and engaged, sitting on the floor all around and talking. And they’re like, ‘Ms. Story, this is so cool. Come see it!’ It’s fun for them to come in here and just become invigorated by their learning.”

But what the kids remember most is that it’s fun. “There’s a buzz in this room,” Wendy says. “Kids are enthralled and engaged, sitting on the floor all around and talking. And they’re like, ‘Ms. Story, this is so cool. Come see it!’ It’s fun for them to come in here and just become invigorated by their learning.”

The makerspace all started with a grant from the Homewood City Schools Foundation written by the school’s technology specialist at the time, Emily Miller. That next summer in 2015 Emily had to move for her husband’s job, but Wendy was starting her first year as assistant principal and had started a makerspace in her former school district. So she and the new technology specialist spent a semester researching and touring other school’s spaces.

From there they started to transform the former broadcast studio and equipment storage room with their vision. Every surface in the room that could would be writeable. Any furniture that could moveable would be moveable. The colors, selected based on research, would be invigorating. It would be filled with tools for learning—including a new 3-D printer the grant funded.

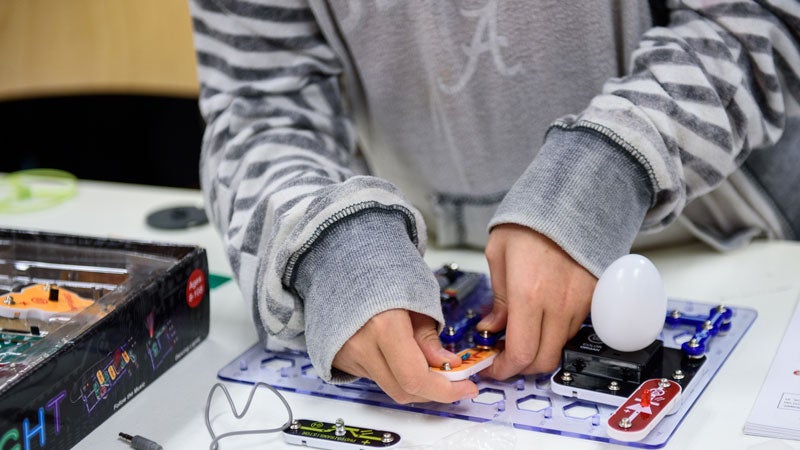

“We brightened up the space and made it a place kids wanted to come to learn,” Wendy says. “When kids come in now and they are doing robotics and we’re doing ramps in third grade with their science standards, we can push things out of the way and they can go to town, or if they need the tables for Makey Makey [circuits] and doing soft circuits, they can use the tables.”

An additional foundation grant given in a later school year expanded the makerspace offerings to provide more robotics tools for grades K-2, more tools to use games to teach coding concepts, and DIY books for self-guided learning for teachers and students.

An additional foundation grant given in a later school year expanded the makerspace offerings to provide more robotics tools for grades K-2, more tools to use games to teach coding concepts, and DIY books for self-guided learning for teachers and students.

The space also exposes teachers to new tools and ideas. Some have already added their own mini makerspaces in their classrooms and added flexible seating as a result. The school is additionally planning to soon have the makerspace room open for students to work on or start independent projects in the mornings before school.

Teachers are always thinking of new ideas for the space with the help of Emily Dunleavy, the school’s technology coordinator. Last year as a second-grade teacher, Emily’s class collaborated with another class to build the Mayflower out of tin foil out cut in certain dimensions. The goal was to see how many pennies each ship could hold when placed in a tub of water. Thanks to popsicle reinforcements inside a tin foil structure, one held 75 pennies. “I felt like my kids were more creative when they came into this space,” Emily recalls.

The uses for the space are endless. After reading about Three Little Pigs, first graders build structures with popsicle sticks, straw, cardboard, tooth picks and construction paper to withstand the test of “wind” from a hair dryer. Third graders program and code robotic toys called Sphero balls and measure its speed down ramps. Fourth graders create “squishy circuits” using bananas and gummy bears, and this year can use new liquid Bare Conductive electrical paint to do so too.

Coding comes to life in fun ways with video game and maze design tools and with board games that teach its basics. With one, students design game elements on a pixilation grid with blue for water, green for land, yellow for coins, etc. and then use an iPad to scan the board and then play their game.

Want to know more about the space? Just ask a Shades Cahaba student. Fifth grader Banks Aycock remembers connecting circuits to create a piano snake where they could tap on different parts and they would make noises. “[The room] opens up my mind to different things I can do,” he says. His classmate Caroline Crigger recalls making animal shelters out of cardboard but not before first sketching their design with Expo markers and finding snap circuits to use to make furniture.

Want to know more about the space? Just ask a Shades Cahaba student. Fifth grader Banks Aycock remembers connecting circuits to create a piano snake where they could tap on different parts and they would make noises. “[The room] opens up my mind to different things I can do,” he says. His classmate Caroline Crigger recalls making animal shelters out of cardboard but not before first sketching their design with Expo markers and finding snap circuits to use to make furniture.

Even just walking in the room makes them feel excited and happy, they say. “It’s a very imaginative space,” Wendy says. “You can have fun and let your imagination go wild.”