Pat Sullivan has had several stops on the road of his life. Nowadays, he spends most of his days on a street some could call Pat Sullivan Memorial Drive. Some could. He wouldn’t.

Alabama Highway 149 in Homewood changes its name three times from the gates to John Carroll Catholic High School to the gates of Samford University. The road is Lakeshore Parkway at John Carroll, becomes West Lakeshore Drive between Interstate 65 and Columbiana Road and is Lakeshore Drive at Samford.

The campuses are separated by 3.4 miles, but they have one thing in common—the man who is memorialized in each place. The football field at John Carroll and the Sullivan-Cooney Family Field House at Samford are named partly for Sullivan, who was a star quarterback for the Cavaliers and a beloved coach for the Bulldogs. And then there is the third monument, outside Jordan-Hare Stadium in Auburn—a statue of the West End native who went on to earn a Heisman Trophy while playing quarterback for the Tigers on the Plains.

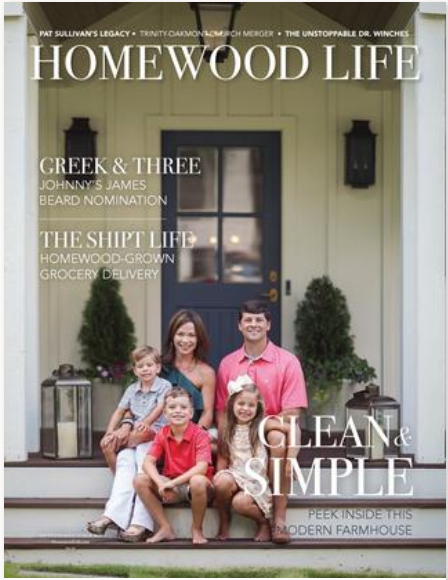

John Carroll’s football field, named in honor of Sullivan. Photo by Sherry Rowe.

But Sullivan, who contracted throat cancer in 2003 but is cancer-free today, doesn’t revel in the well-deserved praise that comes his way. While his office is on the top floor of the Sullivan-Cooney field house, he thinks more about the lives he’s touched than the awards he’s received.

“When I walk in this building, I don’t think about it,” says the Vestavia Hills resident, who is now Samford President Andrew Westmoreland’s special advisor for campus and community development. “When I go to the field at John Carroll, I don’t think about it. When I go to Auburn and by the stadium, I don’t think about it.

“It’s like I’ve always told our players: What you get out of athletics is not the trophies. It’s not the rings. It’s the relationships that last for a lifetime. When I come in this building, I don’t look at it as it being named after me. I feel the relationships I have made through the players and coaches who have come in this building.”

But the adoration that is felt for Sullivan—and his wife Jean —goes much deeper than his success on the field as a player, or on the sideline as a coach. David E. Housel, director of Athletics Emeritus at Auburn, says Sullivan might have receded into Auburn history if he were measured only by his on-field successes.

“But he is loved and respected by Auburn people now every bit as much as he was when he was playing,” Housel says. “He is the symbol of Auburn, the outward and visible symbol of Auburn—in the way he played, the way he coached, the manner he has lived his life and especially in the way he has dealt with his physical challenges.

“You don’t always have to win to show your character,” Housel continues. “Pat has had a setback on [his health], but it has not defeated him. It’s changed him but it hasn’t defeated him.”

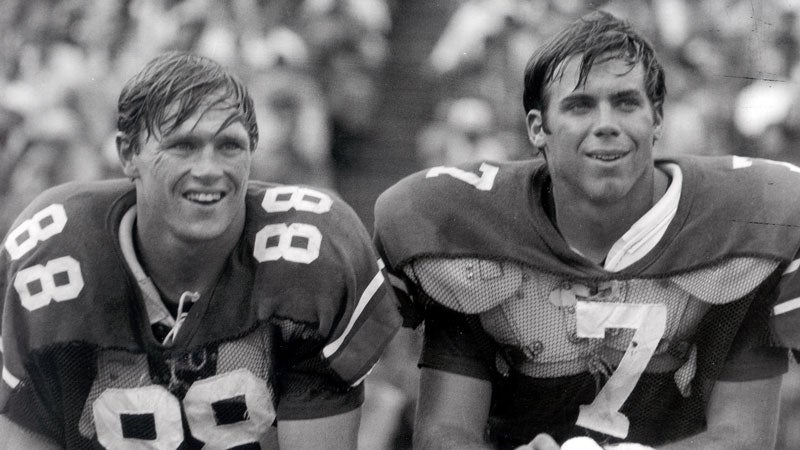

Pat Sullivan, right, during his time playing for Auburn University. Photo courtesy of Auburn Athletics.

An All-American quarterback at Auburn, Sullivan won the Heisman Trophy in 1971 and then played six seasons in the National Football League with the Atlanta Falcons and Washington Redskins. He went on to be a head football coach at Texas Christian University and offensive coordinator at UAB. He ended his coaching career as the head coach at Samford.

Gary Cooney remembers his first varsity play on the football team at John Carroll when the school was on Birmingham’s Highland Avenue and the team played at a stadium on Montclair Road. Specifically, he remembers Sullivan giving him another chance when he missed a key block on his first varsity effort.

“It was his leadership capability, giving me—kind of a geeky sophomore in high school—the confidence that I could do this,” Cooney says. “And it’s served me well in life. For that, I’m eternally grateful for that leadership and that moment.”

Cooney would go on to play football at Samford before eventually becoming vice chairman of McGriff, Seibels & Williams. Years after having played football at Samford, he and his family wanted to honor his parents with the field house. And he wanted to honor his lifelong friend who had become the head football coach there. “We wanted to honor Pat and his family as well,” Cooney says. “During a conversation about that, Pat said, ‘Before we get ahead of ourselves, let me earn that at Samford. When I do accomplish my goals, then we can discuss that opportunity.’”

Sullivan did that. His 47 victories made him the winningest coach in Samford history. “Our family gift was of bricks and mortar,” Cooney says. “The bricks and mortar mean nothing without the heart soul that our coaches, support staff and student athletes bring every day to that field house. Pat and Jean Sullivan provided that leadership, the heart and soul as the head football coach and chief mother of the team. When the bricks and mortar are blended into the heart and soul that the Sullivans injected into our program, then the results are something very special.”

On Team Sullivan, the former coach considers his wife of 48 years —who he met on a blind date shortly after graduating high school—the most valuable player. “The best thing that’s ever happened to me probably in my life is being married to my wife, Jean,” he says. “She’s a godsend. She’s taken care of me through all my illness. She’s not only my wife, she’s my best friend. I can’t say enough about her.”

Sullivan’s health issues—throat cancer and a neck injury that required multiple surgeries—forced him to coach, when he could coach, from the press box instead of on the field on game days. Ultimately, his health led him to leave coaching, but not Samford. Westmoreland saw to that.

“In every sense, he is exactly as he appears to be: a person of intelligence, persistence, wisdom, good humor, with an impenetrable core of ethics that is rooted in a vibrant faith,” the Samford president said in a statement when Sullivan ended his coaching career. “He cares deeply about his family and his student-athletes. He is respectful of every person he encounters.

“I am grateful beyond words for his service to Samford over the past eight years,” Westmoreland continued. “I look forward to continued association with him and with Jean as we seek to provide greater experiences for our students now and in the years ahead.”

Jean Sullivan says her husband’s job at Samford is good medicine for him. “He comes to the office most every day,” she says. “He enjoys seeing the kids and seeing the coaches, going to the games and watching practice. He wants to help the university renovate the stadium. There are still projects he’s working on. He’s retired from coaching but he’s not retired from living, trying to contribute.”

And then there’s his other project. “Jean and I together are also working on a project down at UAB to help people with head, neck and throat cancer that will be able to help them throughout their battle with that disease from the start to the finish of their treatment,” he says. “It will also help them in their battle with the side effects that they have. We’re in the process of getting that all put together.”

Cooney, the former Cavalier and Bulldog player, said the Sullivans “are an incredible team.” His friend’s continuing battle with illness caused him to step away from the sideline as a coach. After accomplishing his goals, the Board of Trustees unanimously voted in favor of the name change to the Sullivan Cooney Family Field House.

“His name, rightfully so, belongs first,” Cooney says of the field house. “At best I was an average athlete and at worst Pat was an incredible athlete, one of the best in the history of the state of Alabama. The gift that Pat and Jean and those coaches have given to our student athletes…that’s where the real teaching begins.”