It starts on a boat. The setting is seemingly familiar—the school they attend every day. But today these sixth graders are dressed as if they live back in 1907 and have an identity card in hand that transports them back in time and to the waters approaching Ellis Island. When it comes time to walk off the boat, a man might ask them to step aside. “Wait, why can’t I go?” the immigrant-in-character likely responds. And that’s when the confusion begins. That’s when the role starts to feel real. That’s when one person’s story diverges from the person next to them.

Or maybe the reality-in-character moment comes students need to have their bag checked or when their baby is crying and must be inspected. Then they will start playing along, start rocking their baby doll. “Wait sir, you have to wait,” the inspector might say. “Something doesn’t look right with your limp.”

“It wakes them up,” teacher Dave Marshall recounts of Homewood Middle School’s annual Immigration Simulation. “They realize this is not going to be a normal day. The story they had planned might not go like they think it’s going to go. (Like the immigrants on Ellis Island), some went through easily and others had to wait and cry out for their children or go back to their homeland.”

Perhaps the most disorienting station of the simulation is one where students face a language barrier. Parent and grandparent volunteers who speak German or Spanish or Arabic or Greek will administer a questionnaire in the language they speak but the students do not. “What?” the kids say. “Huh? I don’t understand.” And yet they have to try to answer questions.

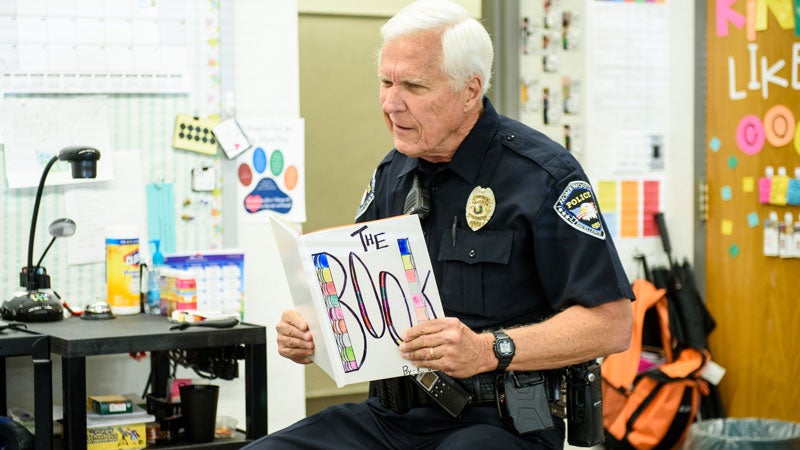

Each year you’ll find Dave and the other sixth-grade teachers in the inspection line, with tools in hand, ready to yell when necessary and otherwise fully act in character. They bear the pun-filled names of Vera Loud, Maddie Lott and Addie Tude to play on their character’s personality. The simulation’s founder, Donna Johnson, who is now retired, was always Inspector Hattie Nuff.

“Like any actor, it starts with research,” Dave says. “This year I focused a lot on the types of diseases that inspectors would be looking for.” He has the immigrants remove their hats so he can look out for lice on the scalp, and he examines their eyes and eye lids and checks their posture watching for signs of a limp, their skin for outbreaks or rashes, their strength to ensure they can work.

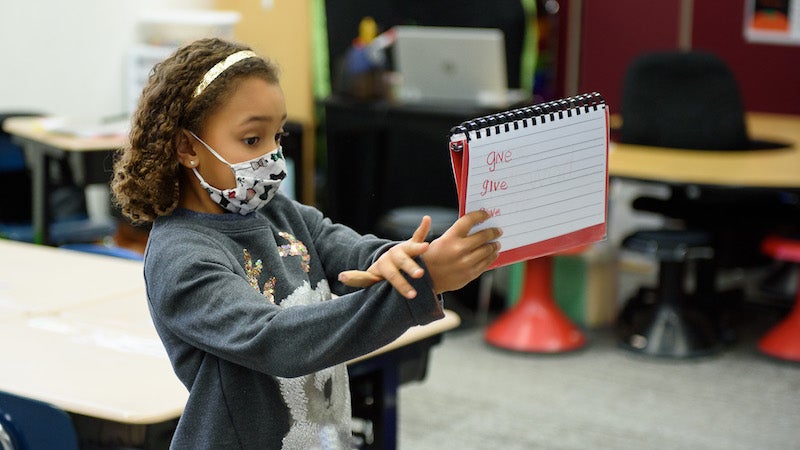

At another station, one of many staffed by parent volunteers, the immigrants’ mental acumen is tested with puzzles and patterns, at another they are given a literacy exam, and at still another they undergo a legal manifest interview to make sure they are who they say they are and know their plans upon arrival.

Once the students make it through all the inspection stations, they find representatives from the Red Cross, Travelers Aid Society, and other organizations with job applications and sign-ups for English classes and housing ready. They can also send a telegram home to tell their family they have arrived in America and exchange their currency into dollars and cents. And before they return to the reality of 2019, students collect their luggage (in the form of their backpacks) and all congregate outside holding American flags to, as new U.S. residents, say the Pledge of Allegiance and sing “God Bless America.”

Each school year HMS sixth-grade social studies classes start their studies in the late 1800s with the rise of industrialization and the growth of cities in the United States—and the influx of European immigrants. “We talk about the hardships they faced, which leads us into the progressive era when there were so many things wrong with the cities that there was a need for social reform,” teacher Darby Baird explains. By October, they are stepping back in time to 1907, the year of highest population shift of that era, and to the Immigration Simulation. Each student is assigned a country of origin, and they pick a name and create an identity for themselves.

For many of the school’s 375 sixth-graders immigration is a foreign process until this day, but for others it’s not all unfamiliar from reality. Darby recalls a student one year whose family had moved to Homewood that year from a Middle Eastern country and who spoke very little English. “The Immigration Simulation was daunting for her, so prior to it (ESL teacher) Ms. (Georgia) Miller and I prepared her for what it was going to look like,” Darby says. “After the simulation she was very happy to talk about the differences in what she experienced versus what the simulation was like.”

When Donna Johnson started the Immigration Simulation, first in her classroom in 2003 and as a sixth-grade-wide event in 2007, she would also lead discussions on similarities and differences between historical immigration and immigration today. “It was interesting to the students to see the parallels, that they needed better lives and better jobs and wanted an education and to leave poverty and religious oppression,” she says. “A lot of that was very similar to what it is today, so that generated a lot of conversation with the students.” And many of them still remember the whole experience today, more than a decade later.

Anna Laws is also quick to note that the Immigration Simulation is a staple of the sixth-grade experience in Homewood. Elementary students hear about it from their siblings and friends, and now when people hear that Anna, who attended Shades Cahaba and HMS before graduating from HHS in 2014, is teaching sixth-grade social studies, they often ask her about the Immigration Simulation. “As a sixth grader I was quiet, and the inspection terrified me,” she recalls. “Now being on this side it’s almost a comical experience to see our kids react differently.”

And she’s learned the part just like Dave, making the kids jump up and down to see if their feet work. “Some kids really love it and some worry that they won’t do it good enough,” she says.

Back when she was in sixth grade, Anna remembers teachers pinching her cheeks before she went into the inspection so she would look healthier. “As a teacher this time I got to do that to a student, so maybe it will stick with them,” she says.

But she remembers more than just pinched cheeks too. “I think it makes you realize how special America was at this time that people were willing to go through so much hardship to come to (here),” Anna says. “It resonates with kids that it is a special place and place worth coming.”