Want to cycle at home? There’s a Peloton bike for that. Want to work out with a gaming console? Try a Wii. Want to weigh yourself to track your health goals? Buy an inexpensive scale. But what if you are a wheelchair user? The answer isn’t as simple. But research at the Lakeshore Foundation is looking to change that.

First off, there’s a Peloton-like bike under development known as AVEED (pronounced “avid” and standing for Advanced Virtual Exercise Environment Devise) that comes with electronic adjustability to fit each rider’s personal setup. You can also turn on the video screen to start a trail ride virtually through trails around Birmingham like Red Mountain Park or use other online riding platforms like Zwift.

Also in the works is a Wii-like gaming board that works across all gaming systems and reduces barriers for all users to play and get exercise. It’s at the same threshold as a door, which allows access to the board without a ramp, and comes with hand rails for those who have poor balance. A new round of testing on it started in January, and those behind the project hope that before long it will be commercially available.

And then there’s a scale that’s in development for wheelchair users. Typically scales for wheelchair users scales cost around $2,500. Thanks to a collaboration with UAB engineering though, there’s a lightweight prototype in development though that would be around a tenth of that price tag with a platform that users would wheel on top of.

But these projects—and a now-completed Apple watch feature—aren’t coming to life in a silo of a research center. In fact, what makes Lakeshore Lakeshore is that its research happens in the same building where around 3,000 people with physical disabilities or chronic health conditions come to for recreation.

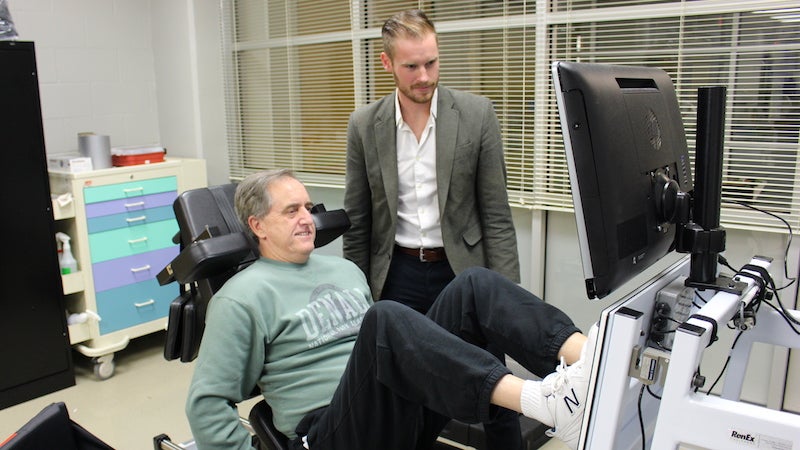

“The people we are developing these interventions for are located right outside our lab door,” says Dustin Dew, Lakeshore’s director of research operations. “We can bring someone in to get their feedback to make sure our research is relevant and that it is something the population wants to happen.

Lakeshore 2.0

When Lakeshore Foundation President Jeff Underwood was hired to work for the fledging nonprofit 28 years ago, its core mission was still the same as it is today—“providing programs for physical activity for people with physical disabilities and chronic health conditions under the premise that sheer movement is so important to stay active and maintain independence and be healthy,” he explains. The foundation had grown out of its neighbor Lakeshore Hospital, which started in 1973, when its staff realized how important it was for people who were discharged from the hospital to stay active.

In short, the Foundation provides physical activity programs not typically found through your local recreation center or YMCA. And while they had certainly done that well for more than two decades, around 2010 its leadership began to see a bigger version of that gap to fill. If they were truly interested in the people they served, they want to take a more holistic approach to address nutrition and mindfulness, and with that holistic approach they wanted to look beyond their campus with research-based program.

“We realized then that there was little hard evidence as to the benefits of the programs we provide,” Underwood explains. “We see everyday people are better because of their experience here but we wanted to put some science behind that for them to be more data-driven. And we wanted it to then be replicated.”

Far beyond Lakeshore Drive there are 61 million people in the U.S. who have some form of disability—that’s a little over a quarter of the population. And Lakeshore wanted to reach more of those people, people who have multiple physical barriers to leave their house and/or don’t have a facility like Lakeshore nearby, which is true of most of the country including some bigger cities. “We also realized a lot of people who fall into our mission who just can’t get here,” Underwood says. “There’s a lot of barriers that a person with a disability has just in getting out of the house and doing everyday things.”

That was when the UAB/Lakeshore Research Collaborative started in 2012 led by Lakeshore Foundation Endowed Chair Dr. James H. Rimmer, a leading expert in rehabilitative science for more than 30 years now working at UAB in the School of Health Professions. Lakeshore works with faculty across UAB including the School of Engineering on design projects, the kinesiology department in the School of Education on movement studies, and the School of Health Professions to help better their students preparing for work in the medical field.

Today around 20 research projects are happening at Lakeshore Foundation at any given time with around $7 million in annual funding as its researchers work closely with UAB’s faculty and students. “We are looking to technology to extend programs beyond what we can do on this campus and broaden the reach and depth of what Lakeshore is doing,” Underwood says.

To house all of this, the Foundation has a new facility addition built to facilitate a more holistic vision and expand its work in tele-health.

Tour de Lakeshore

Our tour of Lakeshore’s new facilities starts in space surrounded by natural greenery from outdoors. Light flows into floor-to-ceiling windows in the Mindfulness Studio that looks much like a typical workout room. Except it’s primary design is to foster calmness for guided meditation and breathing, yoga and tai chi, all centered on getting the mind focused back in a positive way. Each week you’ll find participants in there not just practicing mindfulness but also filling out surveys afterward as part of a pilot project called MENTOR (Mindfulness Exercise Nutrition to Optimize Recovery) funded by the CDC.

Next to it is the Movement Studio, a fancy name for a group exercise room. On Mondays Wednesdays and Fridays dance choreographers lead the class to facilitate cardio respiratory training. It’s being tested for 12 weeks at a time with different functional levels—with those who use a wheelchair or can only use one side of their body. The end goal is to take this kind of class to telehealth and train fitness professionals at local YMCAs to deliver the same class for different functional levels.

“Lakeshore wants to almost put itself out of business because we would love for all fitness centers to be fully inclusive and have that knowledge level to train somebody who has survived a stroke or has a spinal cord injury or has Parkinson’s through exercises,” Dew says. It’s all part of a $5 million, five-year grant through National Institute on Disability Independent Living and Rehabilitation Research. Now that it’s been tested at Lakeshore they will soon roll it out into Greater Birmingham YMCAs.

Beyond the Movement Studio is a Nutrition Lab with kitchen equipment that doesn’t look out of the ordinary until you look closer. One range has buttons that someone can easily use with Braille, while another range has knobs that are better for someone with limited finger dexterity to use. You can also change the height of a table with the press of a button to lower it for one of their many youth participants or someone who uses a wheelchair for mobility, and the ovens open from the side and have buttons within reaching distance for someone who is seated.

Beyond the Movement Studio is a Nutrition Lab with kitchen equipment that doesn’t look out of the ordinary until you look closer. One range has buttons that someone can easily use with Braille, while another range has knobs that are better for someone with limited finger dexterity to use. You can also change the height of a table with the press of a button to lower it for one of their many youth participants or someone who uses a wheelchair for mobility, and the ovens open from the side and have buttons within reaching distance for someone who is seated.

It’s also setup for cooking action, be it a nutritionist demonstrating how to alter recipes to be more healthy, how to cook with one side of your body if it’s been affected by a stroke, or turning on its web conferencing system to train Olympic and Paralympic athletes. (Did we mention yet that Lakeshore is also a Paralympic training site?)

To complete the tour, you’ll stop at a set of five telehealth suites. Each small room is home to a monitor, a web cam, table and chairs and can be used to lead someone in their home in one-on-one exercise or check in on how their exercise using a tablet video is going.

From these suites, another study is looking out how therapy for MS patients compares via telehealth with the therapy on tablet videos vs. in person. This study funded by the Patient Center Outcomes Research Institute has more than 700 people enrolled in the trial from Alabama, Mississippi and Tennessee. “If we can deliver it at home, we can save that participant with MS time from going into a neurology clinic to receive their therapy,” Dew says.

And not far from those rooms is an Innovation Studio where many of these videos are filmed against an infinity wall, giving instruction for everything from yoga to dance. Last year alone they created more 200 videos exercise, nutrition and movement videos.

No matter the project that comes its way, Lakeshore researchers are looking at how to fit their work into the lives of the people they see as they walk into work each day and others like them, always asking, “How can we take the expertise of things happening here at Lakeshore and delivering it to people who can’t make it to a place like Lakeshore?”

“If we are not driving change on a national level and reducing barriers to physical activity for people with a disability, we are not doing what we need to be doing,” Dew says. But we’d say they are.

Lakeshore Foundation by the Numbers

- 92 aquatic, fitness and recreation programs

- 14 local, national and global advocacy initiatives

- 20+ research projects

- 12 competitive sports including wheelchair basketball and rugby, and power soccer

- 1 U.S. Olympic & Paralympic Training Site

- 10 housing units for injured military who come to learn how to pursue an active, healthy lifestyle