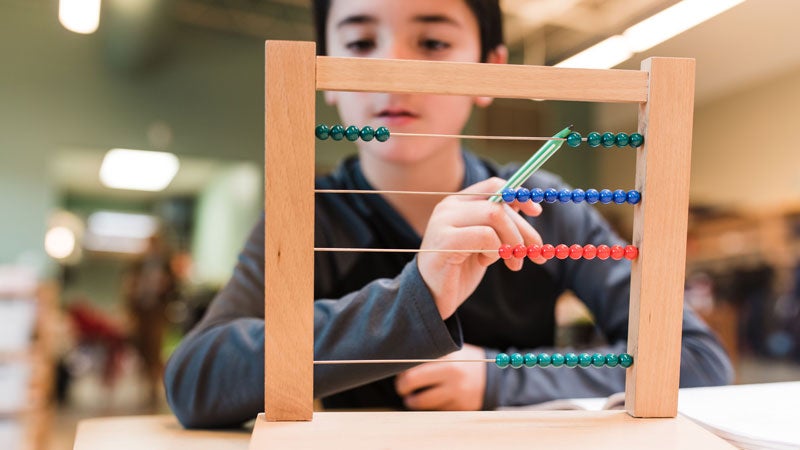

Terra Mortensen didn’t know anything about the Montessori philosophy when she first walked into Creative Montessori School eight years ago. A friend of hers had attended the school in the its early years and had no question that she’d send her own kids there, so she suggested Terra check it out for her then-preschooler. “The first thing I noticed was the diversity,” Terra recalls. “There were Muslim kids and Jewish kids and black kids and Asian kids. Also I noticed the warmth. Everything seemed really small and personal. I saw teachers sitting on the floor with kids and wearing comfortable clothes.”

As soon as her son started kindergarten at the school he cried in the afternoon because he didn’t want to go home from school, and she quickly learned his peers were doing the same thing. In first grade her son asked why he didn’t stay for after care, and when she explained that she didn’t work, he asked her to get a job so he could stay longer. Today that first grader attends the Jefferson County International Baccalaureate School, and although he’s receiving traditional letter grades for the first time, Terra says he entered academically beyond the standards.

But she wasn’t always sure of her son’s education path. “In kindergarten, he had no interest in reading, and I was worried about him,” Terra says. “The teacher said he would catch up when he was ready, and by the Christmas of first grade he was starting to read out of nowhere and it snowballed. By the end of the year he was reading above the level of his public-school peers. The beauty of the Montessori philosophy is that students are allowed to learn at their own pace. Then the same thing happened with my daughter, and I didn’t worry about it that time.”

Barbara R. Spitzer

From the Start

The learn-at-your-own-pace philosophy is the same one the school has upheld for the past 50 years since Barbara R. Spitzer started Creative Montessori with she calls a “selfish” motive. She and her husband had moved to Birmingham from the New York area in the 1960s and couldn’t find a quality licensed day care to send their two children to. So she started her own preschool with a newly minted training for Montessori education she got back in New York.

In 1968, the school started with 18 students, mainly children of parents who worked at UAB and had come from a different state and were already familiar with Montessori education. They met in the Unitarian Church that was in Mountain Brook at the time. As the school grew to 52 children the next year and 80-something the year after that, she began to rent out space in more churches, even after she started an elementary arm of the school in 1971. At one point CMS was located in four different church buildings before they bought the Homewood campus in the late 1980s where they are located now.

More and more, the idea began spreading. “At first I think people thought I was Communist or eccentric, and that didn’t bother me because I knew it was a good education,” Barbara says. “I knew fractions before I took the (Montessori) training, but with concrete materials you can see what is happening and the reason behind it.” The beauty of it, Barbara says, is that each child can go at their own pace. “One child might be more advanced and can progress at their own rate, but they might be at their grade level for other grades.”

Also in keeping with the philosophy of founder Maria Montessori, Barbara wanted her school to include everyone, and that’s how hers became the first integrated private school in the city. “When Birmingham wasn’t so much wanting integration, Mayor Richard Arrington took me into black churches to present the (Montessori) philosophy, and I had two little black girls who enrolled,” she recalls. “One parent said, ‘I knew you were going to integrate but I didn’t know you were going to do that with that many students.’”

Also in keeping with the philosophy of founder Maria Montessori, Barbara wanted her school to include everyone, and that’s how hers became the first integrated private school in the city. “When Birmingham wasn’t so much wanting integration, Mayor Richard Arrington took me into black churches to present the (Montessori) philosophy, and I had two little black girls who enrolled,” she recalls. “One parent said, ‘I knew you were going to integrate but I didn’t know you were going to do that with that many students.’”

Over the years Barbara taught in the classroom too. In the late 1980s she decided to draw on the Latin she’d taken in high school and college and start teaching the language to fourth through sixth graders at the school (although today all students preschool and older take French classes). Then in the late 1990s she introduced a toddler program for ages 18 months to 2.5 years to the school for the first time after training for it in London—and she was the classroom teacher for it too. “I loved the toddlers,” she says. “We planted a garden, and one little toddler who would come early and we’d pick from the garden. To this day she loves cucumbers, and now she’s 20 years old.”

Although she retired in 2005, Barbara remains a board member and comes back to the CMS campus for big events and graduation. Each year she wears a tie dye T-shirt students made for her in the ‘70s and is always eager to hear the students’ speeches about what they liked best about CMS.

A Blossoming Campus

By the time Terra’s kids started at CMS, though, the exterior of CMS didn’t match what she saw inside the classrooms. “When we first came, you had to overlook the preschool building and just look at the classrooms, which were warm and comfortable,” she says. “But the building itself was falling down and leaked.”

The building was designed in the 1950s to be the headquarters for HOAR construction. “We knew what was going on inside the building was priceless, and we wanted an environment that reflected the high quality going on inside the classroom,” says Brook Coleman, past CMS board president and the parent of three former students.

Working with architect and past parent Jay Pigford of ArchitectureWorks, a strategic planning process began. A team of parents worked with students, parents, teachers and community leaders to best understand what the school wanted and needed in a building. As a result, the school launched a successful capital campaign that raised over $3 million for campus renovations. When the preschool building was complete, each new classroom offered access to the outdoors, a lot of natural daylight, and its own bathroom so students don’t have to be interrupted from their work for another student to go use it. A few beloved oak trees from around the campus had to be removed but were repurposed to become paneling and ceilings and benches in the new building.

“(The campus) blossomed into what it is now, which feels like what it was always meant to be,” Terra says. “It’s a light and airy space that maintains the warmth of the classrooms.”

Around the same time, the City of Homewood took note too and renamed the school’s street Montessori Way, and the school also became full members of the American Montessori Society.

It couldn’t be more fitting that the new building was named for Barbara R. Spitzer herself. “She had a vision for something people in Birmingham didn’t realize they needed,” Brooke says. “Her commitment to the Montessori education is embodied in that building. The world changes, technology changes, but the way children learn doesn’t change. That’s why Montessori works.”

It couldn’t be more fitting that the new building was named for Barbara R. Spitzer herself. “She had a vision for something people in Birmingham didn’t realize they needed,” Brooke says. “Her commitment to the Montessori education is embodied in that building. The world changes, technology changes, but the way children learn doesn’t change. That’s why Montessori works.”

Brooke is quick to testify to why as she looks at her children today. Her oldest is a freshman at Yale University and the younger two at are at The Altamont School. “Because they had had teachers that really knew them and trusted them, when they got to Altamont they had no problem reaching out to a teacher for support,” Brooke says. “With the breadth of the Montessori education, they had been exposed to so much art and science and geography and to the world in a way that made the receptive to that (new) environment.”

But perhaps more than anything CMS taught them “that they have the capacity within them to learn as opposed to looking to others to supply their learning,” Brooke says. “The muscle of their interior motivation is strengthened by Montessori. They have a genuine love of learning.”

Now a new set of families are developing a love of learning at CMS just like Brooke’s kids did. Take for example Katherine and Adam Thrower, who moved to Edgewood to be closer to the school after their now-fourth-grader started at CMS in kindergarten. “Since it’s small enough you see preschoolers through eighth grade interact well with each other, and older kids mentor the younger kids,” Katherine says. “They get excited about going to younger kids’ classroom, and it’s neat to see a family dynamic where they all interact together.”

Now a new set of families are developing a love of learning at CMS just like Brooke’s kids did. Take for example Katherine and Adam Thrower, who moved to Edgewood to be closer to the school after their now-fourth-grader started at CMS in kindergarten. “Since it’s small enough you see preschoolers through eighth grade interact well with each other, and older kids mentor the younger kids,” Katherine says. “They get excited about going to younger kids’ classroom, and it’s neat to see a family dynamic where they all interact together.”

Today CMS Director Greg Smith leads a school of 250 kids from 20 different zip codes who drive to their campus in the heart of Homewood every day. (We’d be remiss not to mention that Greg lives in Homewood, was an intern at Hall-Kent Elementary when he began his career, has kids who attend Homewood City Schools and still connects regularly with the Homewood Board of Education.)

This year CMS has added a seventh grade and next year will add an eighth grade, but mostly, Greg says, his job is to continue the legacy of education that began 50 years ago. “I admire Barbara immensely and her being open and inclusive when it was unheard of in Birmingham for a quality preschool education. Our jobs are to uphold that standard.”

Creative Montessori Through the Years

1968

Barbara R. Spitzer founds a Montessori preschool.

1971

Elementary classes are added to the school.

1982

The school’s name becomes Creative Montessori School.

1988

CMS moves to its current campus in Homewood.

2005

Barbara Spitzer retires.

2015

Ground breaks for a new building on the new Homewood campus.

2018

New middle school grades are added to the school.