By Rick Lewis

Photos by Madoline Markham, Contributed

There are vanishingly few people possessive of both a keen eye for design and a raw talent to create, a complex of the eye and the hand, distilling things of arresting visual allure to delicate brushworks on a canvas. However, even fewer people command an ability to create something from nothing—mellifluously imbuing common day objects with an enchanting charm. During his life, Thomas Lindsay, Jr. was one of these rarified creators, a man whose boundless sense of joy for life and art pulled people in like a magnet for living. He was a painter, a designer, a drawer, a gardener, a collector, a salesman, a father and a friend. And until his passing in November of 2020, the Homewood native was always busy with his next project.

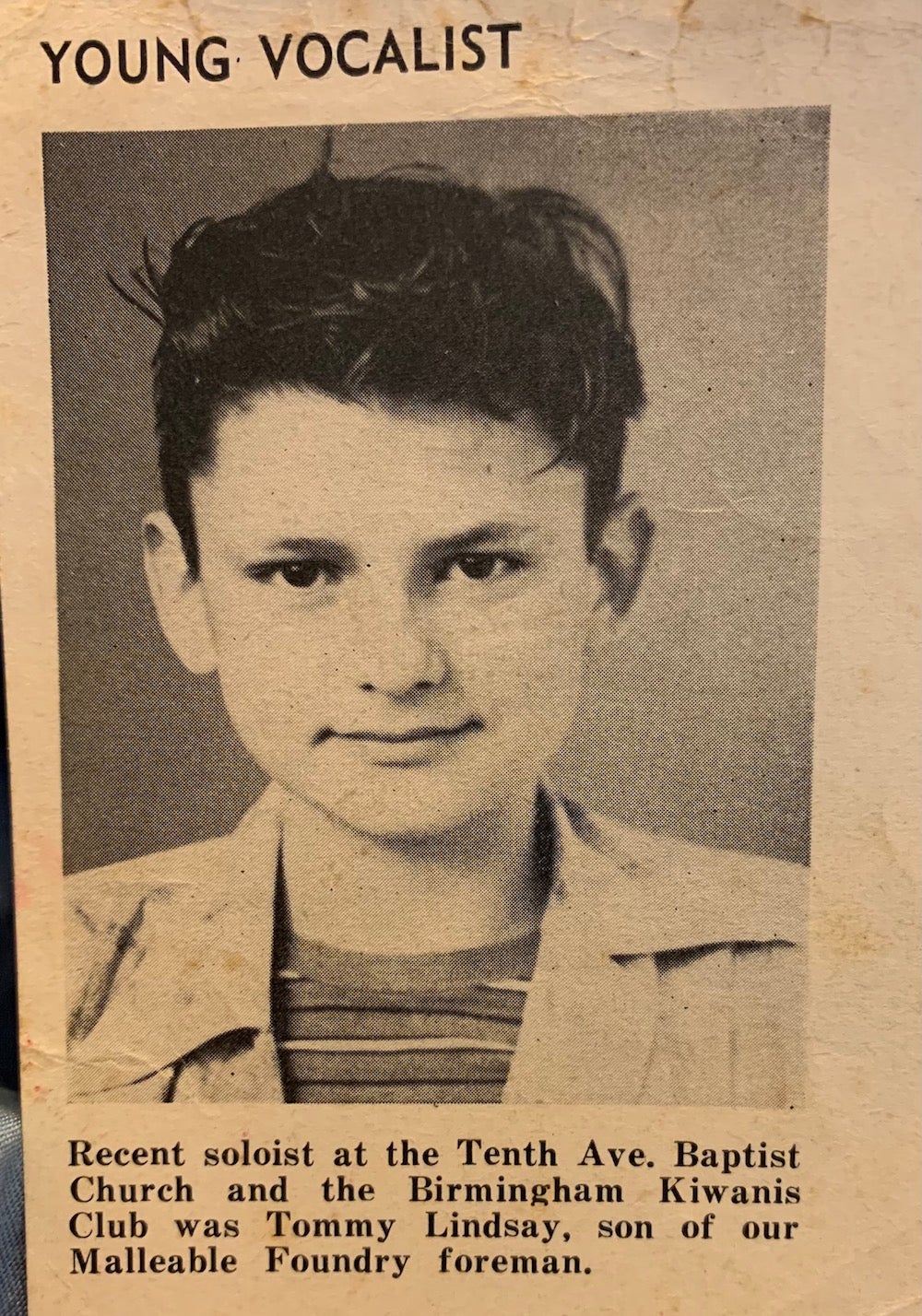

Born in Birmingham in 1935, Lindsay spent his childhood here in a lovely home on Poinciana Drive, and it was here, too, that he was surrounded by such a rich sense of beauty from a young age. Walking the streets of old Homewood, Lindsay saw the varied styles of architecture, the focus on raising a pleasing garden and the effort that people put into cultivating a sense of seemingly natural refinement—all excellent inspiration for a curious mind.

Lindsay attended Shades Cahaba Elementary School and Shades Valley High School but was never the strongest student. It wasn’t until college that he learned he had dyslexia. Instead, Lindsay found creative ways to mitigate his lack of scholastic success. Taking after his mother and great-aunt, who were both artistic in their own right, he created the sets for school plays, designed the yearbook, acted, sang and carried himself with a confidence earned by a natural skill to create.

“Tommy was one of the most talented individuals I had ever seen,” explains Lindsay’s longtime friend and Shades Valley classmate Hayes Hoobler. “He was a thespian, an artist and a designer, and he was just fun to be around.”

So, riding off the high of being chosen as ‘Most Original’ in his senior class of 1954, Lindsay attended the University of Alabama on an art scholarship. There, he had the chance to fully embrace what had set him apart before and dove head-first into finding new ways to explore his visual style with some ventures being driven by necessity. At one point, a lack of money for art supplies inspired his choice to use crinkled, paper grocery bags as canvas, adding an unique layer of depth to his early work.

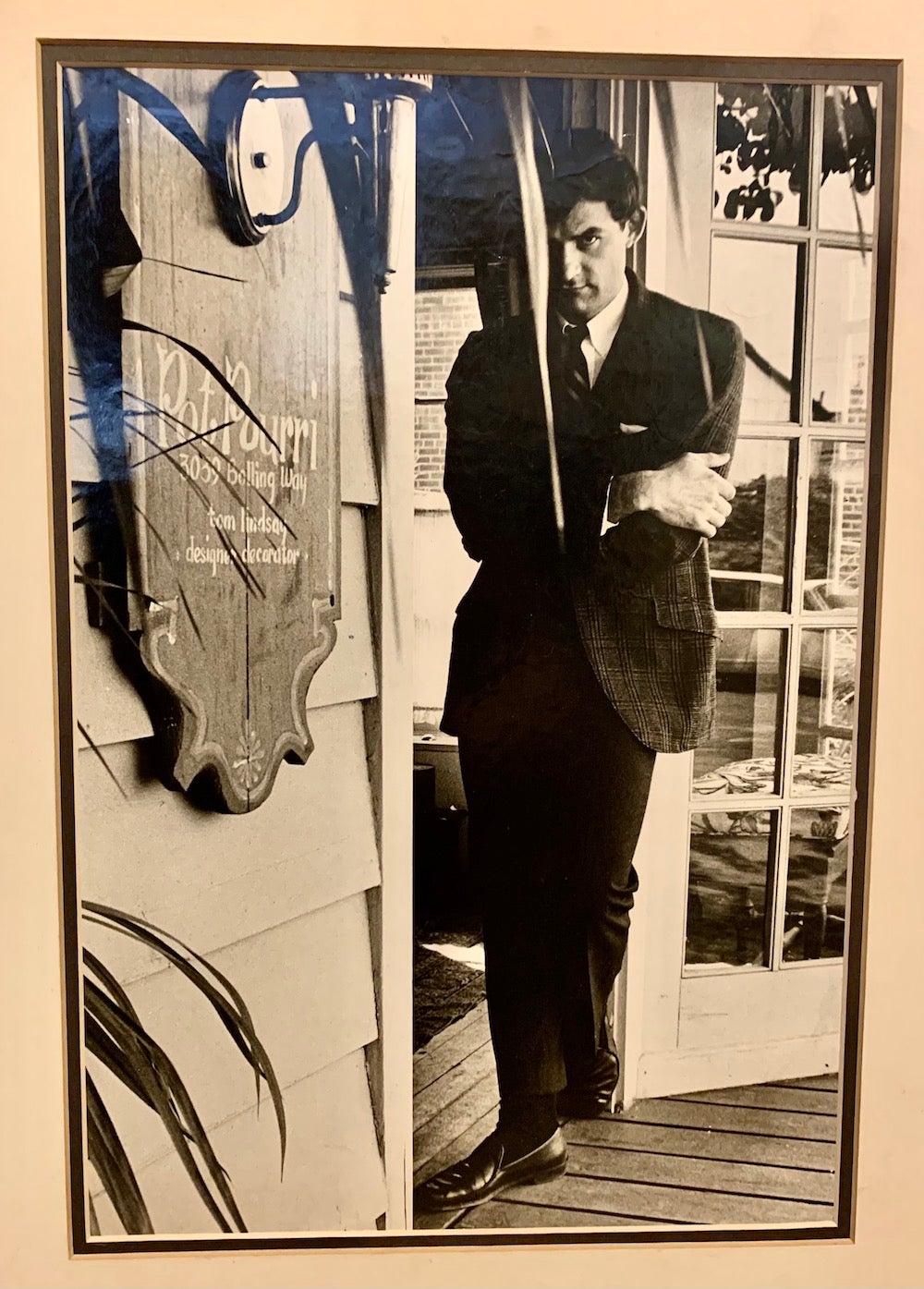

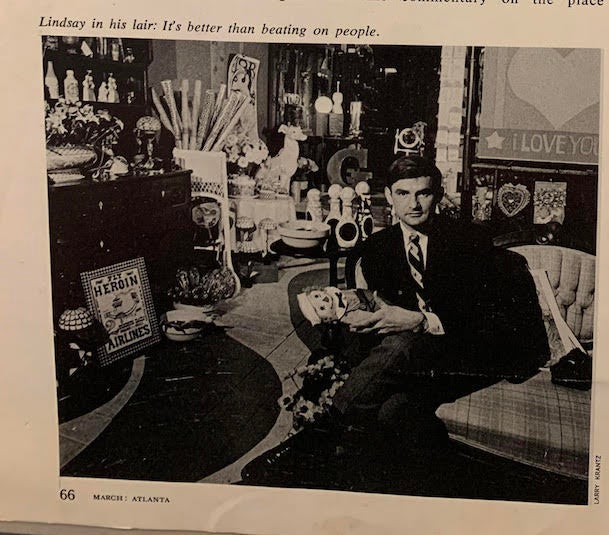

After graduating in 1959, Lindsay moved to Atlanta, Georgia, where he got his professional start in interior design. A few years of designing displays for a department store gave him the confidence to open his first gift store, Potpourri, in Buckhead. Soon after, he opened a new store, Circa 1933, to much fanfare. The store was a mecca for all things both beautiful and off-kilter, and the floors, which were painted by Lindsay, himself, were set in swirling patterns that gave the whole place a lively feeling of movement. It was a different design style Lindsay would practice often, even painting wonderful ‘carpets’ on the wooden floors of his home, tying together rooms with a sense of whimsy.

“I have a magnificent table that he and my brother made for me,” says Toni Skipper, a friend that met Lindsay when they both worked at the Atlanta Merchandise Mart. “It’s a little round table, made out of wood with dropping wooden overhangs that’s painted to look like a draped tablecloth.”

Lindsay’s uncanny ability to unite the odd and the elegant worked perfectly in growing 1960s Atlanta, which was then a union of both the young and old, Southern and cosmopolitan.

“It was a big small town in those days,” says Skipper. “It was vibrant.” Very much, seemingly, like Lindsay himself.

“He was the funniest guy I’ve ever known,” she adds. “He was entertaining, was nice looking—he dressed like a model,” and always had an air of sensitive genius about him. “He told me that he remembered standing in his crib and watching his mother comb her hair. I used to say: ‘Tom, no one remembers that from the crib.’ He would always come back: ‘I remember. I used to love to watch her comb her hair.’ That to me says volumes about a person who has an eye for artistry.”

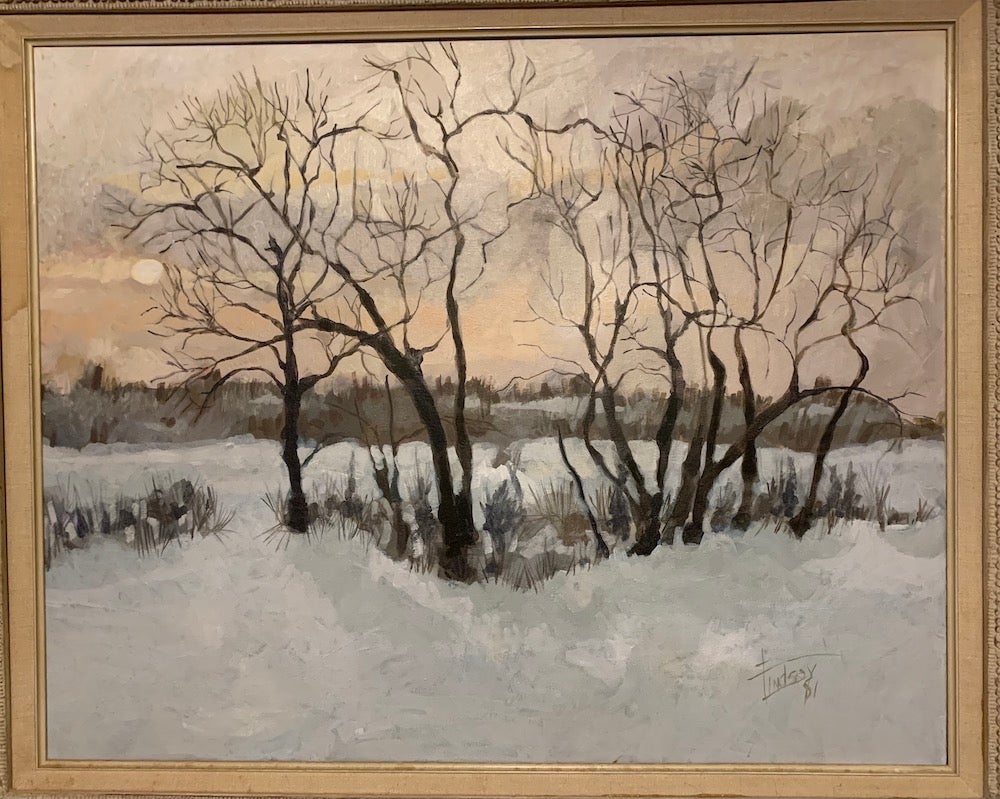

While design work occupied much of Lindsay’s time, he was encouraged to pick up painting again and would find himself most productive in his studio in the early hours of the morning from midnight to 3 a.m. He produced diverse works like earth-toned still-lifes or vibrantly colored semi-abstracts that seemed to capture the life and rhythm in his subjects. Over time, he saw some success–having one-man shows in both Birmingham and Atlanta and traveling across the Southeast with his work.

Lindsay was someone that knew how to occupy time in countless ways—forever keeping his mind nursing an idea, no matter how zany, as his neighbor of many years in Atlanta, Ingeborg Jelley, shares, “my husband was from Wales, and he wanted to put a thatched roof on our garage. Tom thought that was a wonderful idea and tried to come up with plans to build it. He was also trying to build a pool in his backyard, so he could jump from our garage into his pool.”

Lindsay also managed to turn his design expertise into work that would bring a sense of familiar comfort to countless people as director of image and design for Days Inn, putting together portfolios for the company’s non-motel properties. In his role as an independent design consultant, he worked on the Sea Island home of Days Inn CEO and art collector Richard Kessler and was even flown to Saudi Arabia to compete for a job working on a palace. But with everything he did, Lindsay brought a forward-thinking vision to his work.

“He always amazed me that he could come up with some design, and then a year later you could see in magazines the same thing he had thought of before,” Hoobler shares. “He had a touch. He could turn an ugly old house into something picture-worthy. He was ahead of his time.”

While Lindsay was always busy creating, he so often found it was for himself, his family or his friends.

“His work was very unique,” Martha Kiel, Lindsay’s cousin, recalls. “But he didn’t like to talk about himself, and he couldn’t promote his own art.” For Kiel, Lindsay’s talent as an artist that “could make something out of nothing” (even making a dollhouse out of a saltine cracker box) was one that was witnessed by those who knew him best. He might not have had flashy gallery shows throughout his whole career, but he was always in a state of generation, from his early work on canvas to his later collage-based oeuvre.

Lindsay lived a life full of color and charm. One of an easy-flowing beauty that he both built around himself and inspired around those he was with. His contagious sense of wonder with the world often drifted back to his childhood here in Homewood, which is still a place of assorted appeal and a natural charisma. It is a place that inspires an inclination to think more deeply about what makes something catching, and it made the life of Thomas Lindsay that much more rich.