By Madoline Markham

Photos by Lindsey Culver

“What says ‘kah’?” the teacher asks.

“There are two ways to say ‘kah,’” her first graders echo in response as they each place their pointer finger in the tray of sand in front of them. “C says kah,” they say in unison as they write the letter C in the sand. “And K says kah,” they finish, writing that letter next to it.

Hardly a second or two passes before their teacher is on to their next prompt as the kids shake their sand trays.

“Good job!” she says “Clear your board!”

And so the pattern repeats with each prompt: “What says mmm?”* is followed by “What says sss? What says ing? What says ung? What says qua?”

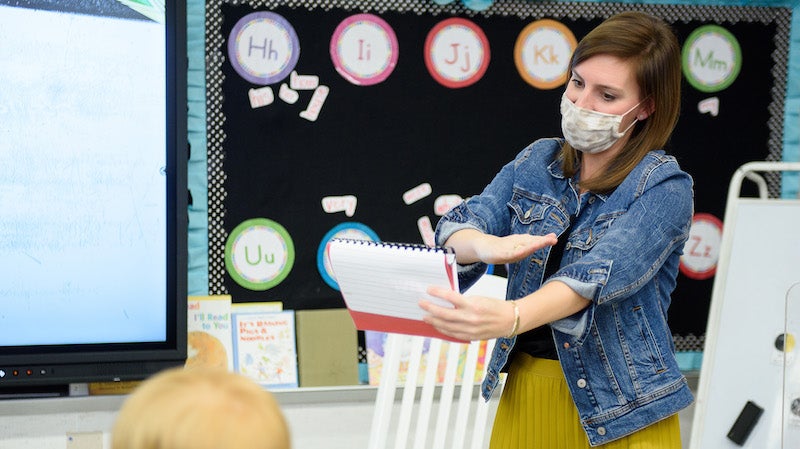

This isn’t how Megan Werner learned to teach reading 15 years ago when she was in college, but she can’t imagine doing it another way now.

Since she went to training for a multisensory approach to reading called Orton-Gillingham three years ago, Werner says she has seen tremendous growth in reading in her students at Shades Cahaba Elementary.

“Some kids learn best by listening, while others learn best by visual clues, others learn best by touching things, and other kids learn best by physical activity,” she explains. “This hits on all of those modes. It’s good for all the kids because they are all learning in the way that is best for them.”

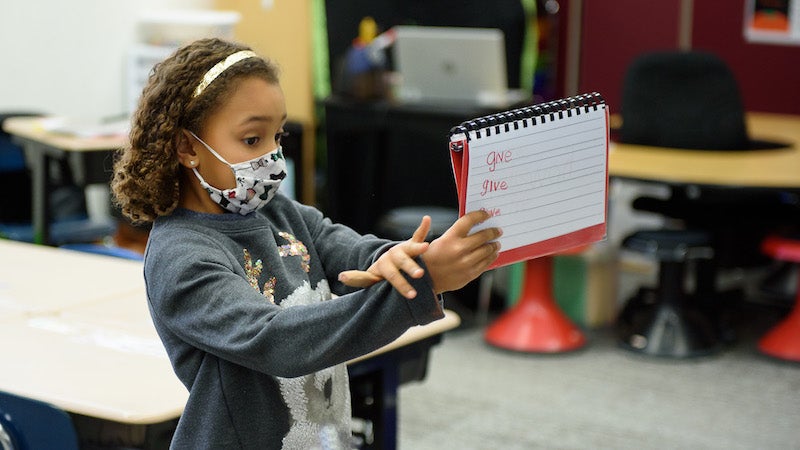

Later in the day, Werner’s students pull out their book of “red words” that don’t follow phonics patterns. “So we just have to memorize them by heart,” she says.

The students hold out the flip book “like a beach ball” in front of themselves with one hand, and use their other hand to tap on their elongated arm. For the word “give,” that’s one tap for “g” up near their shoulder, one for “i” further down toward the elbow, one for “v” still further down and one for “e” almost at their wrist, followed by saying the whole word “give” as they slide their hand from wrist to shoulder.

“It’s like muscle memory,” Werner explains. “If they get the first letter, then it’s like the other ones just come out of their mouth with it. For the words that are five or six letters, we put them to song, so if they can get the first letter, it’s muscle memory too.”

It’s similar to why at other points in the school day her students pound their fist on their desk as they sound out each syllable in a word. “It’s putting that motion to it,” Werner says. “When they are pounding the word, they are breaking it down into the beginning sound, the middle sound and the ending sound, so they can then go back and write it and ultimately read it.”

By contrast, the way Werner taught reading before this training was almost all memorization, she says. She would hold up the letter G, and her students would say “gah.” And that was it, over and over again. But with Orton-Gillingham, which teachers call “OG” for short, “We are using so many of those modes to cement it even more. We are digging deeper,” she says.

And the results are not insignificant. With the fast pace of the lessons, kids pay attention better and get excited about reading every day in her classroom. By the time they move on to second grade, Werner hears from their new teachers what great spellers the students are. Better yet, the instruction style gives students who struggle with reading strategies to use so they can pound and tap to work on reading even when she isn’t there.

Originally Homewood City Schools teachers sought out training in OG for students who are dyslexic or otherwise struggle with reading, but quickly they came to see the method benefits all students, according to HCS Director of Instruction Patrick Chappell. And because of it, classroom learning in the core part of the day helps eliminate the need for students to be pulled out for reading intervention later in the learning process because they have fallen behind. The OG philosophy is approved by the International Dyslexia Association too and on Alabama Literacy Act from 2019.

That change trickles down to middle school too. “What we are seeing now is kids are making more progress in elementary school, and when they are getting to middle school, we are not seeing as many issues,” Chappell says. “They have learned how to accommodate around dyslexia to a much better degree than seven or eight years ago.”

After all, learning to read is no small order. “As adults we tend to think of reading as something that just happens to us, but it’s so abstract and it’s probably the hardest thing any of us learned to do,” Chappell says. “This is breaking things down in a way that makes sure there is a way to not get left behind.”

The physical acts of the learning process, he says, are “making it more concrete and helping a kid link a sound that seems very abstract, particularly to a kid who is struggling and has some sort of reading interference.”

Cristy York, HCS director of student services, also notes how understanding the brain is key to understanding why OG methods work so well for students who might otherwise struggle: “It helps hit on different parts of the brain that those of us who learned to read easily would tap into. It allows them to activate other parts of their brain to work around that deficiency and achieve that same thing.”

Today around 80 elementary teachers in Homewood City Schools have been through the same OG training as Werner. The weeklong session runs 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. each day and costs about $1,200 per person, a price tag often funded through Homewood City Schools Foundation grants. According to Chappell, after a few teachers went through the training initially around seven years ago, a teacher next door would see the practices in action and want to go through it, and it caught on from there as more and more teachers came back saying, “This is the best thing I have ever done. I cannot wait to use this with my students!”

And if Werner’s class is any indicator of students in the rest of Homewood, the students are just as excited as the teachers about it.

*Editor’s Note: According to the Orton-Gillingham philosophy, the letter sound for “mmm” is written as /m/, “ing” is written as /ing/, etc., but for the purposes of the general readership of this article, they have been written out as they sounded to the writer.